Writer in Residence at The University of Edinburgh and current Edinburgh Makar Michael Pedersen is of bloody course much loved for his colourful, full bodied and heart-tugging poetry. His CV lists prize wins and high-end shortlistings aplenty, no time to share them all here. The wonderful collection Oyster, a collaboration with his dear friend Scott Hutchison is an affectionate highlight along with the more recent The Cat Prince and Other Poems.

In 2022, he turned his attentions to penning non-fiction in the form of his book Boy Friends. Springing from his deep affection for Hutchison and the loss of him – the Frightened Rabbit mainstay took his own life in 2018 – within its pages he explored male friendships and masculinity. Looking at pals connected with briefly and short term to lifelong and firm, at affiliations healthy and less so, emotional connections made and lost, hearts broken or full, he flagged them all up. Boy Friends encouraged men and boys to consider relationships they have with each other and sparked conversations about how males live and love. The book meant and means so much to Michael personally and professionally, keeping Scott’s memory precious and goodness, how it opened doors and possibilities. When writing Boy Friends he didn’t imagine it taking off or having the consequences it did. ‘The number of people it’s reached has been so unexpected for me, I still get messages about it. It’s been a risky but beautifully rewarding ride,’ he says over Zoom from his flat in Glasgow.

We’re calling Boy Friends non-fiction but that’s not quite the truth. It’s a genre-bending work, often regarded a novel. ‘Everything I write, it’s all been about storytelling and dissolution of the genres. Some of my favourite poetry is prose poetry, some of my favourite fiction is auto fiction that’s actually non-fiction. I like anything that breaks down boundaries in literature. I smuggled loads of poems into Boy Friends. It’s the same with the novelling, it was always going to be poetical.’

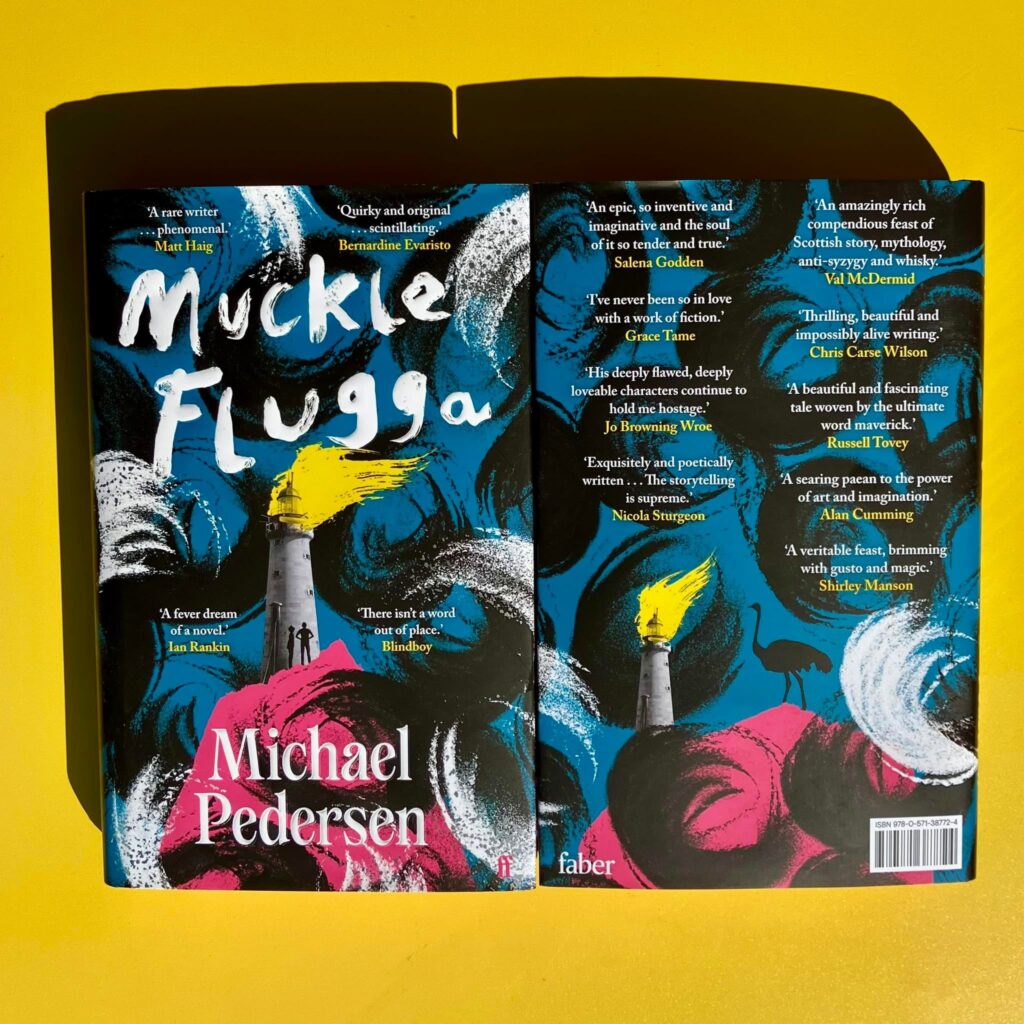

The novel he refers to is Muckle Flugga, his debut, continuing the friendship theme and exploring it further. Michael has always wanted to write a novel, he reveals. He loves poetry, we know that, but reads as many novels as poetry books, he says. ‘I’ve always worshipped at the altar of novels. I spend more time reading novels because the fuckers are longer!’

Muckle Flugga, the audiobook version of which is to be narrated by actor Jack Lowden, is as beautifully written as you’d expect, with language immersing us within the tensions of life and duty in a lighthouse on a remote Scottish island. It centres around a new arrival on Muckle Flugga, Firth a 25-year-old man initially set on taking his own life and instead finding fresh opportunity for himself. He creates the circumstances to build a kinship with Ouse, who in his late teens is trapped in an uncomfortable and often violent co-dependent relationship with his widowed father, The Father. Firth encourages his new pal to leave the island and pursue his dreams in Edinburgh.

‘They’re in the early throes, the courting stage of what could be an exciting friendship love affair and they’re just working that out. They’re getting to know each other in a very intimate, intense space,’ says Michael of the pair. ‘Making big life decisions in each other’s company. It could go either way, they could mean everything to each other really quickly for a small period of time. It’s wanting to give your wall or feeling you’ve given too much too quickly, they’re in that exciting, energy-charged malleable state where this relationship could become many things. For all the worries and the trepidations it causes, it is mostly exciting.’ That’s a lesson learned from Boy Friends, how friendships can become a beautiful permanent presence, but similarly might leave your life. ‘But you might carry them with you. You might leam lessons from these friendships which are integral to your core being,’ he stresses.

Can we say that Firth isn’t always likeable?

‘He’s lost. It was important to me we met someone at their lowest ebb, and they began in their own manner to claw their way back. Their life gets a longer term to it than they initially thought and perhaps has slightly more meaning. They try to sculpt themselves into a better being and for all his flaws and his foibles, tactics and manoeuvring I think he’s well intentioned. He’s aspiring to be a good person and that’s what’s important.’

Michael grins. ‘I’m hopeful for him.’

Michael’s been referred to as a relentless optimist in interviews. ‘I think it was mean to be a slur, but I take it as a beacon of compliments!’

He chose Edinburgh as Ouse’s potential destination of dreams in the book because it’s the ‘antithesis’ of Muckle Flugga. ‘It’s near the English border, it’s the capital city, it has all the funding. All eyes are on Edinburgh and most people there don’t know there is a Muckle Flugga. In The Father’s mind, it’s the nemesis of where they are. It’s the one place Ouse can go where The Father won’t want to follow.’

Muckle Flugga the book is is dreamy with magic, the charming spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson (RLS) appearing to Ouse when he needs him the most. A romantic dandy, his inclusion is in response of Michael’s fond memories of winning the RLS Scholarship ten years ago and enjoying the A Friendship in Letters collection of RLS and Peter Pan creator JM Barrie’s to-and-fro missives. RLS was a man who valued friendship and travel and romanticism. This appealed to Michael. ‘I thought, this lost boy, who could be the most use to him in this point in time? It’s his favourite writer who also happens to have explored the world, suffered from sickness, died too young. He’s a life coach and a confidante.‘

The relationship between Ouse and The Father is problematic, with fear and jealousy respectively butting heads, but there is a sense of care from both sides albeit one unspoken. Ouse nourishes his living parent with food, spends precious time and dedication creating often complex meals for him. ‘He can’t meet The Father on a brawn-to-brawn level like the Father would like, but he can sustain him, he can put goodness in him that makes him a stronger, better more efficient operating version of himself. If The Father was around today, he’d probably have a fast-food diet. It’s such a caring thing, to feed someone in trouble.’ Michael compares it to the inability or unwillingness to find the right words to comfort the bereaved. ‘They might drop off a lasagne at your door and there’s so much in that. It’s another form of language.’

The Father can be bloody awful much of the time, but brings out a chuckle in the reader despite himself. Horribly green-eyed and fearful in equal measure of Firth and Ouse’s burgeoning friendship he empties his bladder into Firth’s bottle of whiskey and wickedly reflects on the younger man enjoying the contents, unawares. ‘‘’How can I slight this guy and him continue to be appreciative of me, not knowing I’ve shunned him!”‘ Michael fancies is The Father’s pleasure in this. Incorporating the incident in the novel is a tribute of sorts to an old uni friend of Michael’s whose father did it to him in revenge for stealing his single malt over a lengthy period. Art imitating life.

The Father needs to read Boy Friends at some point, does he reckon? Maybe find the book in Ouse’s collection one day and have a bit of a sit down and a solid think about himself. Reflect on how he deals with the world around him, and his son.

‘I would like that,’ Michael smiles at the thought.

Another character in the book is in love with The Father, and obviously so. Do you think they could…

‘As a romantic and a relentless optimist, I wouldn’t rule it out!’

‘They are people who are working themselves out that have good and bad traits,’ he says of the characters in Muckle Flugga. ‘I don’t think there’s any black and white villains or heroes. Ouse is probably the closest to being a sweetheart, but everyone has cracks in their seams.’ Firth and Ouse are named after bodies of water, he explains. The River Ouse is famously where Virginia Woolf drowned herself with stones in her pockets, and Firth is a quiet gentle nod to Scott, the Firth of Forth being the place he died. It’s beautiful how the presence of Scott and that beautiful friendship still resonates in his work. Earlier this year as part of Michael’s Makar role he accepted a commission wrote a poem for the Samaritans. ‘They launched a tartan called Samaritan. It’s all about raising awareness to reaching out either to the Samaritans if you need them, or friends or people in your life when you feel you need to talk. If people come to me and it sounds important, I’ll write a poem,’ he explains.

Scott Hutchison and Michael Pedersen (2018)

The Makar, loosely described as poet laureate for Scotland’s capital city, stays in post for three years and Michael’s clearly enjoying the challenge, excitedly sharing what he’s cracked on with so far. Poetry was was something he was embarrassed of and hid from his peers as a boy, he explains. Not because he didn’t love it – on the contrary – but risked getting a ribbing from his class mates upon discovery. As Makar, he wanted a ‘mass fessing up‘ from the offset of writing poetry especially in some of Edinburgh’s inner city state schools, ‘so we can get over it and start enjoying it for the beacon it is’. He launched a poetry competition for school children which he will run and expand each year of his tenure.

Liverpool Playhouse (2024)

As this year’s Independent Bookshop Week Ambassador he has a tour of independent bookshops in June, but before then Michael’s hitting the road with a thorough string of dates to launch and support Muckle Flugga, including a fair chunk with Hollie McNish. His travels include being interviewed by Stephen Fry at the Hay Festival no less. Many good folks who’ve got to know Michael through his poetry have fallen for Muckle Flugga’s charms, Val McDermid, Salena Godden, Alan Cumming, Garbage’s Shirley Manson and Fry eagerly penned blurb for the book.

‘I wanted friendship to be at the core of it,’ he says of the novel. ‘I was in no way finished talking about that.’

Muckle Flugga by Michael Pedersen is published by Faber on 22 May.